Health & Education

We all want the best care possible for our horses. The Heath & Education section covers both Learning Institutions, Organizations as well as many sources for equine assistance including Veterinarians and Farriers.

For those who want a to formally study horses, the Education section includes College Riding, Equine Studies, and Veterinary Schools. Learn about the wide variety of horses in the Horse Breeds section. Supplements and Treatments Therapy are also included in the section.

Everyone can learn from Fine Art and there are some specialty Museums that might surprise you.

Horses as a therapy partner enrich the lives of the disabled. These facilities are listed in our Therapeutic Riding section. To help children and young adults build confidence and grow emotionally, please see the resources available on the Youth Outreach page.

Looking for a place to keep your horse? You can find it in the Horse Boarding section. Traveling? Find a Shipping company or Horse Sitting service if your horse is staying home!

Want to stay up to date with the latest training clinics or professional conferences? Take a look at our Calendar of Events for Health & Education for the dates and locations of upcoming events.

Do we need to add more? Please use the useful feedback link and let us know!

Equestrian World travelled to a remote part of the island more than 100 km from Reykjavik to meet Gunnar Sturluson, an Icelandic Horse breeder and President of FEIF, the International Federation of Icelandic Horse Associations, at his 'Hrísdalur' farm. We also visit Guðmar Þór Pétursson at his farm Hestaland, offering riding tours and instruction all year round.

Read more: The Uniqueness of Icelandic horses, Part 2 (7:15)

By Kentucky Equine Research Staff

Hay produces dust particles that contain mold, endotoxins, mites, and other microscopic antigens. Inhaling those respirable dust particles is the most significant exacerbator of severe equine asthma (SEA). While studies show that hay soaking decreases the production of dust particles, only one study performed to date demonstrates that hay soaking improves lung function.*

In that study, 10 horses with SEA belonging to the Equine Asthma Research Laboratory at the University of Montreal, Canada, were recruited. All horses were in exacerbation at the start of the six-week study. Horses were split into two groups and fed either soaked alfalfa pellets in a feeder or hay that had been soaked in cold water for 45 minutes before feeding at ground level. At baseline and again at the end of the study, airway inflammation was measured via bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL, a “lung wash”), and tracheal mucous scoring was performed. On weeks 0, 2, 4, and 6, researchers assigned respiratory clinical scores based on nasal flare and abdominal effort while breathing. They also measured lung function, as determined by lung resistance/obstruction, during those weeks.

“Clinical respiratory scores and pulmonary function improved significantly during the study in both groups of horses,” explained Ashley Fowler, Ph.D., a Kentucky Equine Research nutritionist.

No significant improvement, however, was noted in airway inflammation in the soaked hay group based on BAL findings of “pulmonary neutrophilia.” This means that a specific type of white blood cell, called neutrophils, persisted in the BAL fluid throughout the treatment period.

“Pulmonary neutrophilia is known to occur when respirable dust exists in the horse’s breathing zone—the two-foot sphere around the nose,” Fowler said.

Despite effectively reducing respirable particles, hay soaking is perceived as cumbersome by many owners, resulting in poor compliance. Further, alternatives to hay soaking such as expensive pellets, oil-mixed hay, and haylage/silage also have limitations. Nonetheless, methods that decrease respirable particles are essential for decreasing the clinical signs of SEA, including labored breathing, coughing, and increased mucus production.

“Because SEA is characterized by inflammation, current recommendations include adding marine-derived anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids to the diet.** Kentucky Equine Research offers EO-3 and ReSolvin EQ, both of which contain EPA and DHA in a palatable formula,” Fowler said.

Owners are also encouraged to decrease dust in the horse’s environment through ventilation and other management practices like turnout and low-dust bedding.

Read more: Beyond Dust Reduction: Soaking Hay Improves Lung Function in Asthmatic Horses

Dr. Janet Beeler-Marfisi

There’s nothing like hearing a horse cough to set people scurrying around the barn to identify the culprit. After all, that cough could mean choke, or a respiratory virus has found its way into the barn. It could also indicate equine asthma. Yes, even those “everyday coughs” that we sometimes dismiss as “summer cough” or “hay cough” are a wake-up call to the potential for severe equine asthma.

Formerly known as heaves, broken wind, emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or recurrent airway obstruction (RAO), this respiratory condition is now called severe equine asthma (sEA).

These names reflect how our scientific and medical understanding of this debilitating disease has changed over the years. We now consider heaves to be most comparable to severe asthma in people.

But what if your horse only coughs during or after exercise? This type of cough can mean that they have upper airway irritation (think throat and windpipe) or lower airway inflammation (think lungs) meaning inflammatory airway disease (IAD) – which is now known as mild-to-moderate equine asthma (mEA).

This airway disease is similar to childhood asthma, including that it can go away on its own. However, it is still very important to call your veterinarian out to diagnose mEA. This disease causes reduced athletic performance and there are different subtypes of mEA that benefit from specific medical therapies. In some cases, mEA progresses to sEA.

What has Equine Asthma got to do with Air Quality?

A lot, it turns out. Poor air quality, or air pollution, includes the barn dusts – the allergens and molds in hay and the ground up bacteria in manure – as well as arena dusts and ammonia from urine. Also, very importantly for both people and horses, air pollution can be from gas and diesel-powered equipment.

This includes equipment being driven through the barn, the truck left idling by a stall window, or the smog from even a small city that drifts nearly invisibly over the surrounding farmland. Recently, forest-fire smoke is another serious contributor to air pollution.

Smog causes the lung inflammation associated with mEA. Therefore, it is also likely that air pollution from engines and from forest fires will also trigger asthma attacks in horses with sEA. Smog and smoke contain many harmful particulates and gasses, but very importantly they also contain fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5.

The 2.5 refers to the diameter of the particle being 2.5 microns. That’s roughly 30 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. Because it is so small, this fine particulate is inhaled deeply into the lungs where it crosses over into the blood stream.

So, not only does PM2.5 cause lung disease, but it also causes inflammation elsewhere in the body including the heart. Worldwide, even short-term exposure is associated with an increased risk of premature death from heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer. This PM2.5 stuff is not trivial!

In horses, we know that PM2.5 causes mEA, so it’s logical that smog and forest-fire smoke exposure should cause exacerbation of asthma in horses, but we don’t know about heart disease or risk of premature death.

Symptoms, Diagnostic Tests, and Treatments

Equine asthma manifests with a spectrum of symptoms that vary in severity and degree of debilitation they cause. Just like in people with asthma, the airways of horses with mEA and sEA are “hyperreactive”. This means that the asthmatic horse’s airways are extra sensitive to barn dusts that another horse’s lungs would just “ignore”.

The asthmatic horse’s airways constrict, or become narrower, in response to these dusts. This narrowing means it’s harder to get air in and out of the lungs. Think about drinking through a straw. You can drink faster with a wider straw than a skinnier one. It’s the same with air and the airways. In horses with mEA the narrowing is mild.

In horses with sEA the constriction is extreme and is the reason why they develop the “heaves line” – they have to use their abdominal muscles to help squeeze their lungs to force the air back out of their narrow airways. They also develop flaring of their nostrils at rest to make their upper airway wider to get more air in.

Horses with mEA do not develop a heaves line, but the airway narrowing and inflammation do cause reduced athletic ability.

The major signs of mEA are coughing during or just after exercise that has been going on for at least a month, and decreased athletic performance. In some cases, there may also be white or watery nasal discharge particularly after exercise. Often, the signs of mEA are subtle and require a very astute owner, trainer, groom, or rider to recognize them.

Another very obvious feature of horses with sEA is their persistent hacking cough, which worsens in dusty conditions. Hello dusty hay, arena, and track! The cough develops because of airway hyper-reactivity and because of inflammation and excess mucus in the airways.

Mucus is the normal response of the lung to the presence of inhaled tiny particles or other irritants. Mucus traps these noxious substances so they can be coughed out, which protects the lung. But if an asthma-prone horse is constantly exposed to a dusty environment it leads to chronic inflammation and mucus accumulation, and the development or worsening of asthma – along with that characteristic cough.

Accurately Diagnosing Equine Asthma

Dr Janet Beeler-Marfisi listening to a horse's lungs assisted by a "rebreathing" bag Veterinarians use a combination of the information you tell them, their observation of the horse and the barn, and a careful physical and respiratory examination that often involves “rebreathing”.

This is a technique where a bag is briefly placed over the horse’s nose causing them to breathe more frequently and more deeply to make their lung sounds louder. This helps your veterinarian hear subtle changes in air movement through the lungs and amplifies the wheezes and crackles that characterize a horse experiencing a severe asthma attack.

Wheezes indicate air “whistling” through constricted airways, and crackles mean airway fluid buildup. The fluid accumulation is caused by airway inflammation and contributes to the challenge of getting air into the lung.

Other tests your veterinarian might use are endoscopy, bronchoalveolar lavage, and in the specialist setting, pulmonary function testing. They will also perform a complete blood count and biochemical profile assay to help rule out the presence of an infectious disease.

Endoscopy allows your veterinarian to see the mucus in the trachea and large airways of the lung. It also lets them see whether there are physical changes to the shape of the airways, which can be seen in horses with sEA.

Bronchoalveolar lavage, or “lung wash” is how your veterinarian assesses whether there is an accumulation of mucus and inflammatory cells in the smallest airways that are too deep in the lung to be seen using the endoscope.

Examining lung wash fluid is a very important way to differentiate between the different types of mEA, between sEA in remission and an active asthma attack, and conditions like pneumonia or a viral lung infection.

Finally, if your veterinarian is from a specialty practice or a veterinary teaching hospital, they might also perform pulmonary function testing. This allows your veterinarian to determine if your horse’s lungs have hyper-reactive airways (the hallmark of asthma), lung stiffening, and a reduced ability to breathe properly.

Results from these tests are crucial to understanding the severity and prognosis of the condition. As noted earlier, mEA can go away on its own but medical intervention may speed healing and return to athletic performance.

With sEA, remission from an asthmatic flare is the best we can achieve. As the disease gets worse over time, eventually the affected horse may need to be euthanized.

Management, Treatment, and Most Importantly – Prevention

Successful treatment of mEA and sEA flares, as well as long-term management, requires a multi-pronged approach and strict adherence to your veterinarian’s recommendations.

Rest is important because forcing your horse to exercise when they are in an asthma attack further damages the lung and impedes healing. To help avoid lung damage when smog or forest-fire smoke is high, a very useful tool is your local, online, air quality index (just search on the name of your closest city or town and “AQI”).

In Canada click here. There is also a visual map of conditions across North America.

Available worldwide, the AQI gives advice on how much activity is appropriate for people with lung and heart conditions, which are easily applied to your horse. For example, if your horse has sEA and if the AQI guidelines say that asthmatic people should limit their activity, then do the same for your horse.

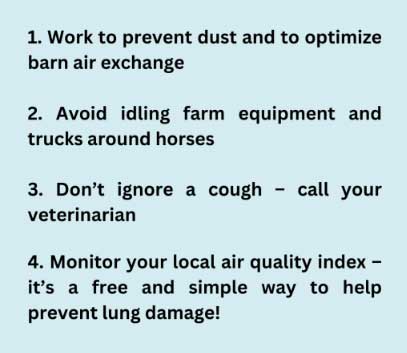

If the AQI says that the air quality is bad enough that even healthy people should avoid physical activity, then do the same for you AND your horse. During times of poor air quality (Image 2), it is recommended to monitor the AQI forecast and plan to bring horses into the barn when the AQI is high and to turn them out once the AQI has improved.

Prevent dusty air. Think of running your finger along your tack box – whatever comes away on your finger is what your horse is breathing in. Reducing dust is critical to preventing the development of mEA and sEA, and for managing the horse in an asthmatic flare. Logical daily practices to help reduce dust exposure include:

- turning out all horses before stall cleaning

- wetting down the aisle prior to sweeping

- never sweeping debris into your horse’s stall

- using low-dust bedding like wood shavings or dust-extracted straw products – which should also be dampened down with water

- reducing arena, paddock, and track dust with watering and maintenance

- when selecting footing substrate, consider low dust materials.

- steaming (per the machine’s instructions) or soaking hay (15-30 minutes and then draining, but never storing steamed or soaked hay!)

- feeding hay from the ground or using hay feeders that sit on the ground

- feeding other low-dust feeds

- avoiding hay feeding systems that allow the horse to put their nose into the middle of dry hay – this creates a “nosebag” of dust

Other critical factors include ensuring that the temperature, humidity and ventilation of your barn are seasonally optimized. Horses prefer a temperature between 10-24 ºC (50-75 ºF), ideal barn humidity is between 60-70%. Optimal air exchange in summer is 142 L/s (300 cubic feet/minute).

For those regions that experience winter, air exchange of 12-19 L/s (25-40 cubic feet/minute) is ideal. In winter, needing to strip down to a single layer to do chores implies that your barn is not adequately ventilated for your horse’s optimal health. Comfortable for people is often too hot and too musty for your horse!

Medical interventions for controlling asthma are numerous. If your veterinarian chooses to perform a lung wash, they will tailor the drug therapy of your asthmatic horse to the results of the wash fluid examination. Most veterinarians will prescribe bronchodilators to alleviate airway constriction.

They will also recommend aerosolized, nebulized, or systemic drugs (usually a corticosteroid, an immunomodulatory drug like interferon-α, or a mast cell stabilizer like cromolyn sodium) to manage the underlying inflammation.

They may also suggest nebulizing with sterile saline to help loosen airway mucus and may suggest feed additives like omega 3 fatty acids, which may have beneficial effects on airway inflammation.

New Research and Future Directions

Ongoing research is paramount to expanding our knowledge of what causes equine asthma and exploring innovative medical solutions. Scientists are actively investigating the effects of smog and barn dusts on the lungs of horses. They are also working to identify new targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and other treatment modalities to improve outcomes for affected horses.

Read more: Air Quality and Air Pollution’s Impact on Your Horse’s Lungs

By Juliet M. Getty, Ph.D.

Stress = Obesity. That’s right. Stress is keeping your horse fat. And the main source of stress for most horses? Restricting forage. The very thing most people do to try to help their horse lose weight actually causes the same stress reaction that brings about body fat retention, and all its attendant problems.

I cannot emphasize this enough

Here are the physiological facts—they are indisputable: The horse is a trickle feeder. He’s a grazing animal designed to chew all day long. His chewing produces saliva, which neutralizes the acid that’s continually flowing in his stomach. Your stomach produces acid only when you eat; your horse’s stomach produces acid constantly, even when the stomach is empty (you see where I am going with this—his stomach should never be empty!). He also needs forage flowing through his digestive tract to exercise those muscles; otherwise the muscles get flabby, which can bring on colic from a weak intestinal tract that torques and intussuscepts. Furthermore, the cecum (hindgut) contains the bacteria responsible for digesting fiber from forage. But its exit and entrance are both at the top! In order for digested material to be pushed to the top, the cecum must be full. Otherwise colic can result from material left at the bottom.

A horse that doesn’t have anything to eat will chew on whatever he can—fences, trees, even his own manure. It’s pitiful to see. Chewing on non-feedstuffs makes a horse mentally acutely uncomfortable because it goes against his instincts, but physically he is in pain and attempting to resolve it. Discomfort? Pain? Stress! And he’s stoic about it. You might look at him and say, “Well, he’s calm.” Sure, he may look that way but it’s an ingrained survival mechanism for horses that are in pain to hide it. In the wild, a horse that shows that he’s uncomfortable often gets left behind by the herd to fend for himself against predators. So anatomically and psychologically, the horse has evolved to deal with pain by simply bearing it. Even the pain of an empty stomach.

What happens when you bring this horse some hay? Against the fear of future deprivation and to relieve his stomach discomfort, he inhales it. Then he waits again for his next meal, even while the acid resumes bathing his empty stomach. And it’s not only the stomach that is affected. The acid can also damage the entire gastrointestinal tract, even making it all the way down to the hindgut. It can lead to colic and it can lead to laminitis.

I have seen hundreds of cases of horses suffering a laminitis relapse through being placed on a restrictive diet. Here’s the scenario: The horse is overweight (maybe even develops laminitis). The well-intentioned veterinarian tells the horse owner, “Put your horse in a dry lot and feed him only a little bit of hay, maybe about 1.5% of his body weight. Give several small hay meals a day, only.” And the rest of the time the horse stands there with an empty stomach. The well-intentioned veterinarian has just given the well-intentioned horse owner the worst possible advice because the stress of that leads to cortisol increase, which causes insulin to rise, and when insulin rises you have laminitis—new, recurrent or chronic. This happens over and over again; it is the unfortunate “conventional wisdom” of the horse industry.

I adamantly protest—this practice is not based on sound science.

When a horse does lose weight through severe restriction, his metabolic rate slows down so dramatically that he can’t process a larger amount of food without gaining back all the lost weight and more when he returns to eating normally. The most likely next outcome is a laminitis attack.

Consider the free choice scenario

First, make sure what the horse is eating is low in NSC and low in calories. Once you know that it’s safe, then give your horse all he wants to eat 24/7, and never, ever let him run out—not even for 10 minutes. Very soon, your horse will eat only what he needs. Yes, at first he may overeat because he’s so excited, but once he realizes he can walk away and come back and figure out it’s no big deal—saying to himself the equivalent of “Yeah, yeah, it’s still there”—he will relax. Perceived starvation is no longer a threat and so his hormones start to calm down. His insulin level starts to drop. His body fat starts to be burned for energy rather than being held onto; his body also responds to the hormone, leptin, which tells him he is no longer hungry. He starts to lose weight, and lo and behold, he actually eats less than he did originally because when he has all that he wants, he knows how much he actually needs. Give him a chance to self regulate. A horse whose system is in healthy balance will not naturally overeat. Give him a chance to tell you what he needs.

Forget the dry lot with no hay

Forget the drastically reduced diet. I have seen this horrible damaging protocol again and again. I understand—it is difficult for horse owners to accept anything else. I am not arguing against restricting calories. Of course you have to do that, but you need to do it by giving a low calorie, low sugar/starch hay.

And you need to increase exercise

Exercise decreases insulin resistance. It also builds or helps protect muscle mass (which is metabolically more active) and certainly it directly burns calories which helps your horse lose weight.

Here’s an analogy: If I told you that you could lose weight by eating all the chocolate cake and ice cream you wanted and lolling around in a lounge chair all day, you would say that’s impossible—even ridiculous—and you’d be right. But if I said that you could lose weight if you chose to eat a lot of low calorie food—if you ate your fill of a variety of vegetables, for example—and got a reasonable amount of exercise, you would think that made sense.

That’s what I’m telling you to do with your horse

Let him eat low calorie foods, all he wants, because that’s what he needs. Help him move around. You get the picture—I hope it makes sense now.

This article originally appeared on Getty Equine Nutrition and is published here with permission.

Find more informative articles in our section on Health & Education.

Teddy Franke will explain the equine vital signs, how to take them safely, and what the ranges should be for each sign. For more information on Certified Horsemanship Association (CHA) visit www.CHA.horse

Read more: Reading the Horse's Vital Signs with Teddy Franke (1:43)

The Fédération Equestre Internationale came to film in Iceland in the summer of 2018, around the Landsmót in Reykjavík. This first part introduces the Icelandic horse and its community.

Read more: The Uniqueness of Icelandic horses - Part 1 (8:02)

- Blanketing the Horse Safely with Tammi Gainer (8:35)

- Riding Exercises to Improve Rider Position with Christy Landwehr from Certified Horsemanship Association (9:50)

- Why Wear a Helmet? Riders Share Harrowing Close Calls

- Monty Robert's 88th Birthday - Cutting (43:03)

- Good Riding Position with Ken Najorka (8:06)

- Four Signs of a Happy Horse

- Seedy Toe White Line Disease

- Core Conditioning for Horses - Book Trailer

- Respiratory Challenges in Horses, Part 1: Equine Influenza

- Horse Blanketing Guide

- FAQ: Is Your Horse Choking?

- Every Horse Needs These Five Things (2)

- Every Horse Needs These Five Things

- Horse Gentler Monty Roberts Tames a Wild Horse In Front of 30,000 Brazilians

- Body Condition Index: New Tool for Objectively Assessing Body Fat in Horses

- 5 Gaits of the Icelandic Horse (2:24)

- Respect the Power of the Horse's Instincts

- Rood & Riddle Stallside Podcast - Pioneering Equine Podiatry with Dr Scott Morrison (38:49)

- Time for a Change: Overwhelmed by the Pyramid? Try the Spiral!

- Three Supplements All Horses Need