by Kristin Pitzer

The life of a performance horse can be unusual, compared to non-performance horses. Show horses tend to travel frequently, can have inconsistent meal and water times, and are often subjected to high pressure situations, such as making the finals at an upper-level event or competing multiple times in a day.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the stress of such a lifestyle can subject these horses to gut health issues. Not only can these problems put a damper on a horse’s career, but they can also become serious quickly and take time to overcome.

Quarter Horse News spoke with Thomas Kellerman, DVM, of Brazos Valley Equine Hospitals in Navasota, Texas, to get more information about performance horse gut health.

Horses were built to graze and eat frequent small meals throughout the day, so their stomachs constantly produce acid to digest all the plant matter they ordinarily would consume. Most horses in training and showing programs don’t have the luxury of constant intake of food, though. Instead, modern management practices usually require them to eat two large meals of grain a day, but if a horse’s diet is lacking in forage, it can create many health issues.

“Frequent intake of forage helps to maintain gastric health in particular,” Kellerman said. “Nutritionists typically recommend a minimum of 1.5 to 2% of a horse’s body weight be fed in quality forage on a dry matter basis per day. Ideally, that amount of forage should be split into at least two feedings per day.”

“Forage” could mean pasture, assuming the pasture has good grass and isn’t a dry lot or full of weeds; grass hays, like coastal, Bermuda or Timothy; or alfalfa hay. While experts agree that horses generally require long-stem forage to slow overall consumption and increase the amount of fibrous bulk that moves through the gut, horses that have dental or respiratory issues, such as equine asthma, may not be able to handle it. Providing these horses with hay pellets, cubes or beet pulp can help them meet their fiber needs while protecting their stomachs from acid.

Even if a horse is eating plenty of forage, there are other things, like the stress of traveling and showing, that can lead to stomach ulcers. These are erosions in the lining of the stomach, varying from small, superficial single lesions to multiple large defects. It is estimated that 50 to 90% of horses have experienced a stomach ulcer at some point in their lives.

Horses with stomach ulcers may show signs of colic, ill-thrift or pain-related behavioral issues. Once diagnosed, they are typically treated with a 28-day course of omeprazole, which blocks stomach acid production. Some horses require up to 60 days of treatment, depending on the severity of the ulceration.

“There is very rapid turnover of the proton pumps, which is why we treat horses with diagnosed gastric ulcer disease daily to keep the stomach pH higher, or less acidic, than it normally would be without treatment,” Kellerman said. “Horses can also develop ulceration in the glandular stomach, which is constantly exposed to gastric fluids. Horses that develop glandular disease are sometimes treated with sucralfate, which almost acts like a liquid bandage to coat the healing tissues, as well as misoprostol, which is a prostaglandin analogue to increase mucosal blood flow.”

While stomach ulcers are a common gut problem in horses, they aren’t the only concern. Colic is another major issue. There are many things that can cause a horse to colic, but research shows that going for several hours without water, staying stalled without turnout, eating a diet that is high in grain and changing environments often — all things that affect show horses — can greatly increase the risk.

Colitis and inflammatory bowel disease also play an important role, especially in horses of performance age. Additionally, certain infectious diseases can affect the horse’s gut, along with parasites, inflammation and tumors. Any time your horse is acting abnormal warrants a call to your veterinarian, but if you see certain symptoms, it’s highly possible something in the gut is the culprit.

“Colic, anorexia, difficulty maintaining body condition, reaction to girthing and behavioral issues are all signs that would cause me to look at a horse’s gastric health,” Kellerman said.

When equestrians think of gut health, they tend to focus solely on the gastric aspects. After all, the stomach plays a large role in a horse’s well-being, and it’s also easy to visualize with a gastroscope, Kellerman said. But a horse’s gut health goes beyond the stomach.

“Every portion of the equine gut plays an important role in their overall health from nose to tail,” Kellerman said. “Even though the small intestine and colon are more difficult to directly examine, they still play a vital role in a horse’s health. Issues such as right dorsal colitis from long term NSAID use, and infectious causes of colitis, such as Salmonella or Clostridial enteritis, can have a massive impact on horses if they develop diarrhea.”

Sand accumulation in the colon, which is often cleared through the use of psyllium supplementation, is common in some parts of the country and can lead to sand colic, chronic diarrhea and weight loss. Veterinarians are also discovering how the use of prebiotics and probiotics can support the horse’s large colon health. A recent area of interest, Kellerman added, is the horse’s microbiome, or natural population of bacteria in their gastrointestinal system, and using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing to target individual therapies to specific horses.

You can’t completely prevent stress if your horse is frequently on the road traveling to shows or rodeos, but there are still management strategies you can utilize to prevent ulcers and other gastric diseases. Kellerman likes to give a preventative dose of UlcerGard to horses to help them mitigate the pressure of being on the road. There are also products available on the market that help buffer stomach acid and chemically decrease the acid content of the stomach for a period of time. Keeping a supply of forage in front of your horse on the trailer and in his stall can also keep stomach acid from building up and creating sores. When on the road, taking several short breaks to give water, rather than powering through the drive, may keep colic at bay. And, by allowing your horse to have mental breaks at shows, even if it’s just to hand graze for a few minutes or walk around to see other horses, you can keep his stress levels down and his mental health stable.

This article originally appeared on Quarter Horse News and is published here with permission.

There are more informative and entertaining articles in our section on Health & Education. While you're here be sure to check out our Curated Amazon Store.

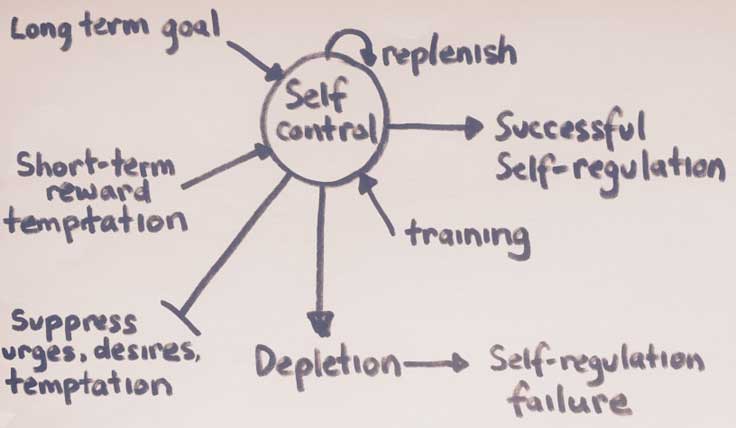

Competition, available for many sports, whether on running tracks, football fields, or in classrooms and boardrooms, has always been more than a battle for victory. It is a reflection of human behaviour, showing how people and teams respond to pressure, structure, freedom, and limits.

At its center, competition is not just about who runs faster, scores more, or thinks smarter. It is also about how one manages the control of the body, mind, environment, and even of the unpredictable outcomes that define contests. Control, in this sense, is not rigid dominance but a balance between discipline and adaptability.

The most immediate aspect of control in competition lies within the self. When the starting pistol fires, what separates the great from the good is not just speed. It is the ability to stay composed under pressure.

The same holds on the racetrack. Of course, Thoroughbreds may train tirelessly on gallops, perfecting stride and pace under controlled conditions. Yet once the gates fly open on race day, the roar of the crowd, the jostling of rivals, and the pressure of the moment can unsettle even the most prepared horse. Here, discipline and the jockey’s ability to steady their mount become the invisible skills to remain focused amid chaos and maintain rhythm when every second counts.

Control of the self is not about denying emotions but channeling them. Anger can fuel determination, fear can sharpen reflexes, and joy can boost confidence if managed wisely. The athlete who loses control of emotions usually loses the match, and the one who transforms them into energy usually writes history.

Trainers are aware that missing a single gallop may not set a horse back, but a pattern of inconsistency in workouts will show up in lost strides on race day. Also, trainers and jockeys understand that raw speed can occasionally win, but consistent conditioning, careful feeding, and proper rest build a champion’s career.

Discipline in horse racing is control turned into routine. It is the unseen cycles of training, stable care, and patient repetition that allow a horse to unleash its peak performance when the gates swing open. As trainers often say, “Races are won in the mornings,” because in those quiet, repetitive sessions, control and rhythm are steadily built.

Interestingly, competition also teaches that too much control can backfire. Horses, like athletes, can mess up when over-managed. A mount held too tightly by the reins often loses fluidity, running stiff and restrained instead of stretching out with natural rhythm. A jockey who becomes obsessed with “not making a mistake” may ride too cautiously, holding back speed at the wrong time.

On the contrary, when a horse finds its stride and the rider senses the rhythm, both seem to glide as if instinct and training have merged. Letting go at the right moment by allowing the horse to run freely becomes just as important as the discipline instilled through months of conditioning. The interesting thing about control in racing is that mastery happens when discipline transforms into instinct, creating freedom rather than rigidity.

This balance is visible in every contest. Trainers can design the programme, set the pace in workouts, and plan the race strategy. However, once the gates fly open, jockey and horse must feel the flow, respond to rivals, and sometimes abandon the script. True control on the racetrack is therefore unique, shifting effortlessly between structure and spontaneity.

No matter how carefully a horse is conditioned, racing carries elements beyond anyone’s control. They vary from track conditions to rival tactics, gate breaks, weather, or even the draw of a difficult post position. These external forces test the horse’s ability to respond and the jockey’s capacity to adapt.

Sometimes a sudden downpour makes the turf heavy, a rival horse presses the pace too hard, or a break from the gate goes poorly. In such cases, riders and trainers face a choice: to either dwell on the uncontrollable or adjust quickly and concentrate on the factors they can influence, like timing the move, conserving energy, and seizing the right opening. This resilience is perhaps one of the deepest lessons horse racing offers, echoing life itself. It teaches us that success does not usually depend on controlling every circumstance but on mastering one’s response to them.

Beyond physical exertion, competition shines a spotlight on the mind. In horse racing, mental toughness applies to both jockey and horse. It means staying calm despite a poor break, a fierce rival, or shifting track conditions.

Control of the mind is central. Without it, strength falters. Just as a powerful horse needs steady hands, a strong body without focus is like speed with no direction.

Competition also reveals how control works within partnerships. In racing, success is not just about a horse’s speed. It also encompasses the seamless communication between jockey and mount.

Trust, timing, and coordination often outweigh raw power. Many trainers and owners face the challenge of balance. Being that too much interference stifles instinct, while too little structure risks disorder. Effective leaders share control, guiding without constraining.

Competition is instructive when control slips. A horse may bolt from the gate too early after weeks of careful training, or a jockey mistimes a closing run and loses by a nose. These moments sting, but they also bring clarity. They show the fine line between rhythm and recklessness, composure and collapse. However, the lesson lies not in the loss itself but in the reflection afterward.

The reasons lessons from competition resonate behind sports are simple. Life itself is competitive. From job interviews to tryouts and academic exams, we constantly face situations that reflect the uniqueness of tracks and fields.

Yet the same principles apply. Self-control helps manage emotions in stressful conversations. Discipline sustains progress in long-term projects. Balance of control and freedom breeds creativity. Adaptability ensures resilience in uncertain environments. Shared control strengthens collaboration in teams.

With these, competition becomes a metaphorical classroom. One that teaches us that control is not about domination but about harmony. Harmony between discipline and spontaneity, self and environment, leaders and groups.

Competition teaches us that control is less about conquering others. It is more about guiding yourself wisely when uncertain. Control, then, is not the opposite of freedom. It is the art of directing it. In life, as in sports, victory usually belongs to the one who understands when to hold firm, let go, and adapt rather than who dominates most aggressively. Perhaps, this is the greatest lesson competition leaves with us all, long after the medals are handed out and the crowds go home.

Read the review from Gambling Insider GGBet to enter UK market.

There are more interesting articles in our section on Racing & Wagering.

Renowned equine podiatrist, Dr. Scott Morrison, head of the Rood & Riddle Podiatry Center, discusses the role of the foot in supporting the horse, and shoeing considerations for different footing surfaces. Rood & Riddle

by Kentucky Equine Research Staff

The type of bedding you provide affects your horse’s health and comfort, as well as your bottom line. From straw and pine shavings to paper and peat moss, the perfect bedding has yet to be discovered. One of the most recent options available is hemp hurd, a byproduct of hemp fiber production.

Two studies presented at the 2025 Equine Science Symposium examined the physical characteristics of hemp hurd and its potential as a horse bedding material.*,**

A research group from the University of Kentucky investigated the water-holding capacity, bulk density, and ammonia-binding capacity of several fiber-type hemp hurd varieties. The study found differences in physical characteristics based on variety and particle size (large vs. small), suggesting that some types of hemp hurd may be better suited for bedding than others.

The second study compared the water absorbency and fecal coliform (Escherichia coli) counts of hemp hurd bedding with two commonly used alternatives: pine shavings and cut straw.

To measure fecal coliform levels, each bedding type was mixed with manure and dissolved urea (simulating urine), then composted for one week. The compost mixtures were submerged in water to create a “compost tea,” which was tested for E. coli using colony-forming units (CFU) as the measurement. Cut straw produced the highest CFU counts (i.e., more E. coli), while hemp hurd resulted in the lowest.

To evaluate absorbency, all three beddings were soaked in water, drained, and weighed. Hemp hurd was twice as absorbent as pine shavings and only slightly less absorbent than cut straw.

“These studies highlight the positive attributes of hemp hurd as a bedding for horses. Further research on the use of hemp hurd bedding in practical and commercial settings is warranted,” said Catherine Whitehouse, M.S., a nutrition advisor for Kentucky Equine Research.

“Don’t ignore the importance of bedding selection to optimize horse comfort and health, waste disposal and management, as well as barn hygiene. Appropriate bedding selection is particularly important for horses with equine asthma,” said Whitehouse.

Do you have questions about the best management and nutritional strategies for horses with equine asthma? Contact a Kentucky Equine Research nutrition advisor to learn more.

*Lee, A., A. Endfinger, R.C. Pearce, and L.M. Lawrence. 2025. Physical characterization of hemp hurd varieties to assess suitability as bedding. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 148:105553

**Williamson, K., A. Jaqueth, K. Ely, G. McGlinch, and S. Jacquemin. 2025. Potential of hemp hurd bedding for use in equine operations. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 148:105436.

Reprinted courtesy of Kentucky Equine Research. Kentucky Equine Research is an international equine nutrition, research, and consultation company serving horse owners and the feed industry. Our goals are to advance the industry's knowledge of equine nutrition and exercise physiology, apply that knowledge to produce healthier, more athletic horses, and support the nutritional care of all horses throughout their lives. Learn more at Kentucky Equine Research.

There a more informative articles in our section on Health & Education. While you're here be sure to visit our Curated Amazon Store.

by Natalie Gasper

The Great Boot Height Dilemma If you’re anything like me, you’re always checking out other riders’ footwear in the barn aisle. After all, boots are a key component of a good ride, which means it’s important to choose the best pair. But how do you choose between a short boot and a tall boot?

Riding boots come in a range of heights, from short boots to tall boots. Short boots are generally ankle height and tall boots usually go to the knee. For Western riders, there’s a convenient mid-boot option that comes to about mid-calf. Many riders will wear different boots for practice than for show.

While both short and tall boots are appropriate for riding, many riders prefer the stability and protection of a tall boot.

Boot height definitions vary somewhat between English and Western riding disciplines. In general, a short boot is no taller than mid-calf, more commonly ankle height. Tall boots are mid-calf and taller (though they often hit just below the knee).

English riding boots are most broadly separated into short boots (paddock and some muck boots) and tall boots.

Practice

When schooling, many riders may opt for a paddock boot and a pair of half chaps. More advanced riders may school in a leisure pair of tall boots. And some riders will hop on in a pair of muck boots (make sure they have a one-inch heel!).

Show

Shows almost always require a tall boot. At some of the lower levels, paddock boots with half chaps are acceptable.

Western boots have a wider range of heights, so it can be more challenging to find the right height. A pair that works great for chores may not be the right height for riding.

There are three main western boot heights.Short (6” – 9” uppers)

Pros: Short boots, like Ropers, are a more recent design that also tends to have a lower heel. They are very comfortable for doing barn chores and the designs tend to feature flexible soles for improved fit.

Cons: The tops have a habit of getting stuck on the saddle’s fender, which can be annoying.

Mid (9” – 11” uppers)

Pros: Mid-height boots offer the best of both worlds, being equally suited for working and riding. The heels tend to be a bit lower than other styles, which makes being on your feet all day a breeze. Plus, the soles usually have treads and cushioning (anti-slip + comfort for the win).

Cons : These boots tend to be more affordable than other options, which means they can have a cheaper look. They’re also not as intricate in their designs as other boots.

Tall (12”+ uppers)

Pros: These boots are similar in many ways to mid-height boots. The heels tend to be higher, and riders often love the ankle and calf support & protection of these boots. Plus, at a higher price range, the designs tend to be stunning and the leather of great quality.

Cons: Depending on the exact height, tall boots may be too tall for showing (the taller the boot, the bulkier they tend to look under pants). Many of the taller boots (13”+) may be better suited as fashion boots than functional riding boots.

Q: Are tall boots better for riding?

If you’re an active competitor in eventing, dressage, hunters, or jumpers, tall boots are worth the investment. Otherwise, a short boot (like a paddock boot) works just fine.

Q: How tall should riding boots be?

This really comes down to personal preference. For English riders, some love them tall and others prefer a shorter boot. For Western riders, you’ll want a slightly taller boot (10+ inches) to avoid stirrup and saddle issues.

Q: What are the benefits of tall boots?

Tall boots can prevent pinching or chaffing from the stirrup leathers, while providing extra protection (and extra warmth in the winter). Some riders feel tall boots keep their legs more stable.

Q: When should I get tall boots for riding?

Tall boots are expensive, so wait to invest in a pair until you’re moving up the levels or in a consistent show program.

This age-old debate will likely never be settled, so don’t be afraid to experiment with boot height to figure out what works best for you.

This article originally appeared on Horse Rookie and is published here with permission.

You can read more interesting articles in our section on Tack & Farm.

Our Mission — Serving the professional horse person, amateur owners, occasional enthusiasts and sporting interests alike, the goal is to serve all disciplines – which often act independently yet have common needs and values.

Equine Info Exchange is totally comprehensive, supplying visitors with a world wide view and repository of information for every aspect related to horses. EIE provides the ability to search breeds, riding disciplines, horse sports, health, vacations, art, lifestyles…and so much more.

EIE strives to achieve as a source for content and education, as well as a transparent venue to share thoughts, ideas, and solutions. This responsibility also includes horse welfare, rescue and retirement, addressing the needs and concerns of all horse lovers around the world. We are proud to be a woman-owned business.